In the Victorian period, the theory of 'separate spheres' for men and women developed. The man's sphere was the world outside the home, where he was to go and earn a living to keep his family. The woman's sphere was the domestic. She was to be the 'Angel in the House', managing the household and providing the moral influence for the family.

In practice, this applied only to women who could afford not to work, and not all of those. Many well to do women were engaged outside the home in what would today be called social work or voluntary work, relating to health, sanitation, education and many other aspects of life.

For women who worked, the home was also considered to be their proper sphere; domestic service was the most highly approved of occupation for women who needed to earn money. It was also the area in which most women were employed.

Many women worked as teachers and governesses. There were large numbers of dressmakers, seamstresses and needlewomen.

Records such as the census returns, however, show individual women employed in a wide range of occupations. Large numbers of girls and women were employed in the textile industries of Lancashire and Yorkshire. The 1851 census records cotton reefers, cotton knitters, cotton spinners and power loom weavers.

There were still remnants of older industries. Mary Murray and Charlotte Atkinson were handloom weavers in Cumberland.

The straw plait industry employed many women and girls in Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire. Susan Bunker, aged 66, was a straw plaiter. Kate Hill, aged eighteen, was a straw bonnet sewer. In another regional industry, Elizabeth Pope, aged fifteen, was an apprentice painter of earthenware in Staffordshire. Jane Baddley, 71, was a 'potter paintress'.

Women were not permitted to work underground in the mining industry, but they worked on the surface. Ann Donald, 78, was a copper miner and Mary Wearn, sixteen, a miner girl, both in Cornwall. Jane Wotton, 82, was a coal miner in Staffordshire.

There were women farmers, with land varying from fewer than ten acres to over a hundred, employing men and boys. Women were also agricultural workers labouring in the fields.

Other women were employers in industry. Susan Garside, 49, chain maker, employed twelve girls in Warwickshire.

Susan Dorrington, 29, was a theatrical performer in Warwickshire. Mary Hutton, 25, was a student at the Birmingham School of Design. Susan Harley, 37, was a bookseller's assistant in Warwickshire.

Women were hawkers, pawnbrokers, 'dealers in small wares'. Elizabeth Fenwick, 21, ran a stall in a bazaar in London.

More unusual occupations were 'wood screw nicker' (Pamela Haycock, nineteen, Worcestershire), 'horn button cutter', Susan Dandy, 26, Warwickshire, and 'watchmaker dial painter', Pamela Simpson, 30, London.

Perhaps the most unusual of all was Jane Gardner, aged 78, of London. Born in Carolina in 1773, she gave her occupation as 'American Loyalist'. She herself was only a small child at the time of the American Revolution; one can only imagine what the circumstances of her upbringing were, for her still to be unreconciled to it in her old age.

Historians have, to some extent, to look at the bigger picture, to deal with statistics and percentages. Novelists can, and should, remember that behind every statistic is a person with a rich and unique history. It should be possible to tell a story about any one of the women mentioned here, or about any of the millions of other women whose names are recorded in censuses, parish records and trade directories.

My published novels

Friday 11 December 2015

Wednesday 11 November 2015

'Romance Flamboyant and Youthful'

This is an eminently unliterary age, incapable of thought, and therefore seeking to be amused. Whereas the the writing of books was once a painful act, it has of late become a trick very easy of accomplishment, requiring no regard for probability, and little thought, so long as it is packed sufficiently full of impossible incidents through which a ridiculous heroine and a more absurd hero duly sigh their appointed way to the last chapter.

Whereas books were once a power, they are, of late, degenerated into things of amusement with which to kill an idle hour and be promptly forgotten.... Who troubles their head over Homer or Virgil these days - who cares to open Steele's 'Tatler' or Addison's 'Spectator', while there is the latest novel to be had, or 'Bell's Life' to be found on any coffee-house table?

Few writers in any age would be likely to agree that the writing of books has 'become a trick very easy of accomplishment.' Critics in any age however are likely to compare their literature unfavourably with that of the past. The lines above were spoken by the hero of The Broad Highway, by Jeffery Farnol, published in 1910, and set in the Regency period.

Jeffery Farnol was a prolific writer of romantic and swashbuckling historical fiction. His titles include My Lady Caprice, Black Bartlemy's Treasure, Adam Penfeather, Buccaneer, and The Geste of Duke Jocelyn. He, or his publishers, described his works as 'a romance of the Regency', 'a stirring pirate story', 'a mystery story of merry England'.

Farnol was a bestseller in his day, but one could ask 'who troubles their head over Jeffery Farnol these days'? I remember shelves of his books in my local library in the 1960s and 1970s, but his popularity was already declining in his lifetime. At his death in 1952, his obituarist in the Times wrote:

For the moment the taste for the romance flamboyant seems to have been superseded - and not necessarily by a taste for anything better. Even those who sniff patronizingly at his novels admit that he achieved something more than the costume and prose style of Wardour Street. Whatever else his books lack... they flow with untroubled zest and assurance.

Farnol's flowery prose style, the relatively slow pace of some of his work, his romanticised view of English rural life in the past, would be assumed not to appeal to modern readers, who are supposed to have shorter attention spans and to require more realism in their fiction (although there is nothing wrong with a little romanticism, and fiction need not always be realistic).

Farnol has a niche following today, but as a bestseller he is largely forgotten. Which of today's prolific and successful writers of historical fiction will be remembered? Will people still be reading Bernard Cornwell or Philippa Gregory in fifty or a hundred years' time? Or will they come to be regarded as out of date as readers move on to the next fashion in historical fiction?

Whereas books were once a power, they are, of late, degenerated into things of amusement with which to kill an idle hour and be promptly forgotten.... Who troubles their head over Homer or Virgil these days - who cares to open Steele's 'Tatler' or Addison's 'Spectator', while there is the latest novel to be had, or 'Bell's Life' to be found on any coffee-house table?

Few writers in any age would be likely to agree that the writing of books has 'become a trick very easy of accomplishment.' Critics in any age however are likely to compare their literature unfavourably with that of the past. The lines above were spoken by the hero of The Broad Highway, by Jeffery Farnol, published in 1910, and set in the Regency period.

Jeffery Farnol was a prolific writer of romantic and swashbuckling historical fiction. His titles include My Lady Caprice, Black Bartlemy's Treasure, Adam Penfeather, Buccaneer, and The Geste of Duke Jocelyn. He, or his publishers, described his works as 'a romance of the Regency', 'a stirring pirate story', 'a mystery story of merry England'.

Farnol was a bestseller in his day, but one could ask 'who troubles their head over Jeffery Farnol these days'? I remember shelves of his books in my local library in the 1960s and 1970s, but his popularity was already declining in his lifetime. At his death in 1952, his obituarist in the Times wrote:

For the moment the taste for the romance flamboyant seems to have been superseded - and not necessarily by a taste for anything better. Even those who sniff patronizingly at his novels admit that he achieved something more than the costume and prose style of Wardour Street. Whatever else his books lack... they flow with untroubled zest and assurance.

Farnol's flowery prose style, the relatively slow pace of some of his work, his romanticised view of English rural life in the past, would be assumed not to appeal to modern readers, who are supposed to have shorter attention spans and to require more realism in their fiction (although there is nothing wrong with a little romanticism, and fiction need not always be realistic).

Farnol has a niche following today, but as a bestseller he is largely forgotten. Which of today's prolific and successful writers of historical fiction will be remembered? Will people still be reading Bernard Cornwell or Philippa Gregory in fifty or a hundred years' time? Or will they come to be regarded as out of date as readers move on to the next fashion in historical fiction?

Friday 30 October 2015

Work in Progress

The time comes when writer stops thinking that he or she will never manage to sort out the mess that is the first draft of the current work in progress, and begins to see a point in time, in the not too distant future, when it will be finished.

It's an exciting time, because one can look forward to having a new book published, and to starting another one.

The only difficulty is deciding what to write. One of the advantages of being self-published is that one can choose for oneself, without having to worry about whether a particular genre or subject is currently considered marketable.

On the other hand, it can be a disadvantage, because one has to decide for oneself, without the benefit of discussion with an agent or editor who knows about trends in book buying, and about what else is due to be published in the next year or so.

A self-published writer cannot - or should not - wait to see how the current work in progress will sell before deciding what to write next; in digital self publishing, the emphasis should be on getting the next book out as quickly as is consistent with quality, so that readers don't forget one's name.

So, should I write another book about this set of characters, or that set of characters? What about another standalone, similar to the already published one that's been doing quite well? Or that new genre and pen-name I've been thinking about?

Or I could start work on one of my shiny new ideas.

Of course, there is always a shiny new idea to distract the writer away from the work in progress. I have a lot of respect for writers such as Dorothy Dunnett and J. K. Rowling, who conceived multi-volume sagas with ongoing storylines and saw them through to the end - in J. K. Rowling's case, while also dealing with the demands of a new marriage and new babies, overseeing the production of the films, and worldwide fame.

Realistically, I know that the shiny new ideas (currently three of them) need a lot of thought and planning before I can begin writing. While I know the characters and settings, I have no idea of plots!

Of course, if one listened to the doom-mongers who claim that the e-book boom is over, and the Kindle is dead, one wouldn't bother to write anything at all. But the ideas would still be there, so why not write them down and put them out there?

It's an exciting time, because one can look forward to having a new book published, and to starting another one.

The only difficulty is deciding what to write. One of the advantages of being self-published is that one can choose for oneself, without having to worry about whether a particular genre or subject is currently considered marketable.

On the other hand, it can be a disadvantage, because one has to decide for oneself, without the benefit of discussion with an agent or editor who knows about trends in book buying, and about what else is due to be published in the next year or so.

A self-published writer cannot - or should not - wait to see how the current work in progress will sell before deciding what to write next; in digital self publishing, the emphasis should be on getting the next book out as quickly as is consistent with quality, so that readers don't forget one's name.

So, should I write another book about this set of characters, or that set of characters? What about another standalone, similar to the already published one that's been doing quite well? Or that new genre and pen-name I've been thinking about?

Or I could start work on one of my shiny new ideas.

Of course, there is always a shiny new idea to distract the writer away from the work in progress. I have a lot of respect for writers such as Dorothy Dunnett and J. K. Rowling, who conceived multi-volume sagas with ongoing storylines and saw them through to the end - in J. K. Rowling's case, while also dealing with the demands of a new marriage and new babies, overseeing the production of the films, and worldwide fame.

Realistically, I know that the shiny new ideas (currently three of them) need a lot of thought and planning before I can begin writing. While I know the characters and settings, I have no idea of plots!

Of course, if one listened to the doom-mongers who claim that the e-book boom is over, and the Kindle is dead, one wouldn't bother to write anything at all. But the ideas would still be there, so why not write them down and put them out there?

Labels:

writing: general,

writing: writing a novel

Saturday 3 October 2015

'The sunlight sparkled on the sea'

Clichés are often clichés for a reason. Sometimes they really do describe what is happening in the most concise and expressive way. The sunlight is sparkling on the sea.

However accurate it might be, the writer who included this phrase in a piece of descriptive writing might be accused of being lazy or unimaginative. But how else would one describe it? 'Ribbons of silver light were reflected off the water'? 'The sunlight created an ever changing pattern of silver light on the waves'? Verging on the pretentious, one feels.

It is a challenge for a writer, to set the scene and create atmosphere, while avoiding the extremes of cliché or purple prose, or, God forbid, becoming a candidate for the Bulwer-Lytton Awards.

These days, a digital camera is almost as essential to a writer as a laptop. Digital cameras are small enough and light enough to be carried everywhere and can be used to record anything that catches the attention. Whether it's a scene like the one above, derelict buildings, a document in a record office, a street scene,

an interesting building,

or an overgrown graveyard,

a writer can build up his or her own reference library of images.

Describing sound is another challenge. Is it possible to improve on Matthew Arnold's description of waves breaking on a shingle beach?

However accurate it might be, the writer who included this phrase in a piece of descriptive writing might be accused of being lazy or unimaginative. But how else would one describe it? 'Ribbons of silver light were reflected off the water'? 'The sunlight created an ever changing pattern of silver light on the waves'? Verging on the pretentious, one feels.

It is a challenge for a writer, to set the scene and create atmosphere, while avoiding the extremes of cliché or purple prose, or, God forbid, becoming a candidate for the Bulwer-Lytton Awards.

These days, a digital camera is almost as essential to a writer as a laptop. Digital cameras are small enough and light enough to be carried everywhere and can be used to record anything that catches the attention. Whether it's a scene like the one above, derelict buildings, a document in a record office, a street scene,

an interesting building,

or an overgrown graveyard,

a writer can build up his or her own reference library of images.

Describing sound is another challenge. Is it possible to improve on Matthew Arnold's description of waves breaking on a shingle beach?

Saturday 27 June 2015

When one is a crime and mystery writer -

- when one visits a garden,

no matter how well laid out,

how well tended,

how well planted,

how colourful,

one is always on the lookout for

a place to hide the body!

no matter how well laid out,

how well tended,

how well planted,

how colourful,

one is always on the lookout for

a place to hide the body!

Sunday 21 June 2015

Who shall we kill?

I've seen several versions of the story in which someone overhears two people discussing the best way to kill someone. The eavesdropper is always highly alarmed, until it's revealed that the conversation is actually about the plot of a book or a play.

Crime and mystery writers find themselves in this situation every time they begin a new book. Who shall we kill and how shall we do it?

First, is it necessary to kill anyone? Dorothy L. Sayers, one of the greats of the Golden Age of British crime and detective fiction, wrote one book in which nobody died and others in which there was no murder.

In an Agatha Christie type mystery, the murder happens near the start of the book. The character who is murdered was created solely for that purpose. He or she has no other function in the story. The reader will not have come to know the victim well. He or she is often an unsympathetic character whose death is not greatly regretted by those around him or her.

What about other types of crime or mystery novels? Is it essential to have a murder?

A murder, or at least a suspicious death, increases the tension. It raises the stakes; the investigation must succeed, or there will be a murderer going free, with the possibility of more deaths. A murder increases the danger for the character who is investigating the mystery, especially if he or she is an amateur sleuth.

If the death happens some way into the book, the victim's character will have been developed to some extent. His or her relationship to the central characters will have been established.

If the victim was an unpleasant person, will anyone, whether the reader or a character within the novel, care very much about his or her death? Will it have any dramatic or emotional impact?

If the victim is someone who was close to the investigator, that will increase his or her determination to solve the mystery and catch the criminal. On the other hand, if the victim was close to other characters in the story, they have to be allowed time to grieve, and also to deal with the practicalities surrounding a death. There is a danger that the plot is neglected while this is happening, and the pace of the story is slowed.

And more importantly, if a writer kills a character whom readers have come to know and like, there is a risk that they will be alienated. They might not finish the book. They might not want to buy any more books by that author.

It might be the case that, in the author's opinion, killing that character is absolutely the right thing to do in the context of the plot. Should the author go with what feels right for the book, or do what is most likely to please readers?

So, who shall we kill?

And more importantly, if a writer kills a character whom readers have come to know and like, there is a risk that they will be alienated. They might not finish the book. They might not want to buy any more books by that author.

It might be the case that, in the author's opinion, killing that character is absolutely the right thing to do in the context of the plot. Should the author go with what feels right for the book, or do what is most likely to please readers?

So, who shall we kill?

Saturday 13 June 2015

The Omnibus Murder available on Kindle

London 1878: Tamar Fleet is proud of her job. She rides the London omnibuses, helping to prevent pilfering from the omnibus company. While the country is deeply divided about whether Britain should go to war with Russia, Tamar takes no interest in world affairs, but occupies herself with her work and her friends.

Then there is a murder on an omnibus and Tamar is drawn into events which may have their origins thousands of miles away. There is trouble for her friends and Tamar has to make decisions about duty and loyalty and face danger herself.

See more at Amazon.

Labels:

history: London,

history: transport,

writing: historical fiction,

writing: writing a novel,

writing:crime fiction

Tuesday 9 June 2015

Memories -

I've been having a clear out of some childhood memorabilia and came across my album of Brooke Bond Picture Cards of British Costume. The cards came in packets of tea and one could send away for an album to stick them in.

As an adult, I can see that this was a well-produced collection. Many of the images were taken from well known paintings and the text on the back of each card and in the album was written by Madeleine Ginsburg, a leading fashion historian.

Back then, the priority was to complete the collection. There was always an elusive card or two that never turned up in the packets at our local Co-op or Liptons. I remember having multiple copies of the Victorian lady in blue. but never getting two of the medieval cards. I finally acquired them from a family friend.

I also came across some of my very early writing. Some I remembered, some I had forgotten. It was interesting to read through and see how my style was developing in my early teens. I was already using a lot of dialogue. Originality was not a strong point, however; most of it was heavily influenced by whatever I happened to be reading at the time.

Now I don't know what to do with it. I certainly don't intend ever to show it to anyone else, but can't quite bring myself to rip it up and throw it out for recycling. It will probably go back in the cupboard and continue to take up space for a while longer.

One does not have this problem with computer files!

Monday 4 May 2015

'His head literally exploded.'

According to the current Writing Magazine, the latest edition of Fowler's Dictionary of Modern English Usage says it's now acceptable to use 'literally' in a metaphorical sense. So what word does one use when one wants to say that something literally did happen?

No-one is going to think that someone's head literally did explode (unless, I suppose, it's a battlefield scene). But what if someone was literally dancing with rage? Or was literally as white as a sheet? Was he or wasn't he?

I'm currently editing the novel I hope to publish soon, a crime/mystery set in Victorian London. One piece of advice to writers that I've found useful, and am trying to put into practice, is to be sure to extract every last piece of drama and tension from a scene. This obviously doesn't apply if two characters are discussing the case over a cup of tea. But if the heroine is in peril, then give her even more reason to be afraid, make the consequences of failure even more catastrophic. Without, one hopes, tipping over into purple prose and Gothic horror!

I'm also checking that all the small details of the plot hang together. When cutting, or changing the order of scenes and events, it's easy for something to fall through the cracks, so a crucial piece of information wasn't shared when it should have been, or one character tells another about something she has not yet done.

Then it will be one final read through for typos, missing punctuation marks, and so on, before uploading.

Then on to the next one.

No-one is going to think that someone's head literally did explode (unless, I suppose, it's a battlefield scene). But what if someone was literally dancing with rage? Or was literally as white as a sheet? Was he or wasn't he?

I'm currently editing the novel I hope to publish soon, a crime/mystery set in Victorian London. One piece of advice to writers that I've found useful, and am trying to put into practice, is to be sure to extract every last piece of drama and tension from a scene. This obviously doesn't apply if two characters are discussing the case over a cup of tea. But if the heroine is in peril, then give her even more reason to be afraid, make the consequences of failure even more catastrophic. Without, one hopes, tipping over into purple prose and Gothic horror!

I'm also checking that all the small details of the plot hang together. When cutting, or changing the order of scenes and events, it's easy for something to fall through the cracks, so a crucial piece of information wasn't shared when it should have been, or one character tells another about something she has not yet done.

Then it will be one final read through for typos, missing punctuation marks, and so on, before uploading.

Then on to the next one.

Monday 16 February 2015

Spring Cleaning

It isn't officially spring for several weeks yet, but here in south east England the first signs are appearing. Snowdrops and crocuses are in flower and daffodils are on their way. On a couple of days it's been warm enough to entice one into the garden to do some pruning and weeding.

On cold wet days there's always something to clear out or tidy up indoors. I've recently been going through some papers which go back decades. I found some cuttings from local newspapers that I evidently found interesting enough to keep at the time.

Now, thirty years later, the advertisements are more interesting than the articles I originally saved.

In 1985 a lady's lambswool sweater cost £17.99. Tweed trousers with turn-ups were £29.99. The great thing about fashion that season, women were told, was the element of choice it offered. Next had four distinct looks; Cross Country, for the independent woman, Dressed for Success for the influential woman, Beatnik Girl for the street look, and Night Club.

Fashion might have been catering for the independent and successful woman, but the toy department sold a 'Housewife Set, complete with brush & pan etc.' for £1.25.

In household fabrics, a single sheet was £6.50. A pair of pillowcases was £3.49. A bath towel was £4.99.

I'm not sure if thirty piece bone china teasets or sets of lead crystal sherry glasses are much in demand in 2015. In 1986 they cost £29.95 and £4.99 respectively from one shop.

The new Renault 11 could be bought for between £5,000 and £6,000 cash, depending on the model.

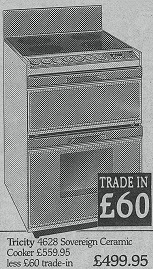

While many, if not most things, have increased in price over thirty years, others, especially technology and household appliances, have become cheaper, both in relation to incomes and in absolute terms.

One dealer in electrical appliances had microwave ovens starting at £129. At time of writing, Currys cheapest model is £39.99. A fridge-freezer was £152. Currys current cheapest is £169.99. (Regrettably, Currys choose to spell their name without an apostrophe.)

An automatic washing machine could be had for £159 upwards, a tumble drier from £136. Twin tubs and spin driers were also available.

All these goods could be bought in the High Street, with no need to go to an out of town retail park. And of course, online shopping was unheard of.

Labels:

history: research,

history: social history

Wednesday 4 February 2015

When is a story not a story?

Short story writing is a specific skill quite separate from novel writing. It is a skill that I do not have, so I've asked my friend Helen Spring to share her thoughts on what makes an effective short story. Helen is a novelist and a short story writer. Her work, including her latest publication, a collection of short stories, is available on Amazon. See what Helen has to say below, and if you agree or disagree with her thoughts, please leave a comment.

WHEN IS A STORY NOT A STORY?

ANSWER: When it is almost any other kind of writing. There must have been more differing opinions written about short stories and their structure than almost any other kind of writing. I have my own opinion about short stories, and when I have voiced it, have received comments which ranged from ‘Utter rubbish!’ to ‘You are so right!’

I think we all have an idea of what a story is, and we always know if we have enjoyed it after reading it. So you may feel I am making a difficulty where there is none. But I can enjoy a piece of writing without agreeing that it is a short story. It may simply be a piece of very good writing describing something which happened – in that case I would call it an anecdote. If it was writing which described something in great detail I might call it an essay. So what does a piece of writing have to have which makes it (in my view) a story?

I believe a story worthy of the name has to have a structure which works through the writing so that the reader has a certain reaction at the end, and knows it is a story. Not necessarily ‘a beginning, a middle and an end,’ although that is a good structure, but something has to change during the narrative to make it into a story.

For example: ‘It was very cold, so I decided to buy some warm cloth and make myself a coat. It took me seven years to make but I eventually had a warm coat.’ – That is an anecdote.

But: ‘It was very cold, so I decided to buy some warm cloth and make myself a coat. It took me seven years to make but by then I had put on so much weight I couldn’t wear it.’ – That is a story.

P. D. James probably put it best when she argued: ‘A short story does not have to have a plot, but it does have to have a point.’ So many short stories these days (and many of them are published) seem to me to be just an interesting (or not) piece of writing with very little structure.

WHEN IS A STORY NOT A STORY?

ANSWER: When it is almost any other kind of writing. There must have been more differing opinions written about short stories and their structure than almost any other kind of writing. I have my own opinion about short stories, and when I have voiced it, have received comments which ranged from ‘Utter rubbish!’ to ‘You are so right!’

I think we all have an idea of what a story is, and we always know if we have enjoyed it after reading it. So you may feel I am making a difficulty where there is none. But I can enjoy a piece of writing without agreeing that it is a short story. It may simply be a piece of very good writing describing something which happened – in that case I would call it an anecdote. If it was writing which described something in great detail I might call it an essay. So what does a piece of writing have to have which makes it (in my view) a story?

I believe a story worthy of the name has to have a structure which works through the writing so that the reader has a certain reaction at the end, and knows it is a story. Not necessarily ‘a beginning, a middle and an end,’ although that is a good structure, but something has to change during the narrative to make it into a story.

For example: ‘It was very cold, so I decided to buy some warm cloth and make myself a coat. It took me seven years to make but I eventually had a warm coat.’ – That is an anecdote.

But: ‘It was very cold, so I decided to buy some warm cloth and make myself a coat. It took me seven years to make but by then I had put on so much weight I couldn’t wear it.’ – That is a story.

P. D. James probably put it best when she argued: ‘A short story does not have to have a plot, but it does have to have a point.’ So many short stories these days (and many of them are published) seem to me to be just an interesting (or not) piece of writing with very little structure.

Please don’t think I am advocating some sort of moral message, although earlier short stories often did have them, for example children’s stories (Cinderella, The Three Bears, or Aesop’s fables.) All these have survived so long because they made a point which the reader understood. These days you wouldn’t get far trying to moralise in a story, but the description of actions or thoughts and their consequences (often unforeseen) can make for an interesting and satisfying structure.

If one studies acknowledged masters of the short story, (I am thinking of Guy de Maupassant or the American writer O. Henry, for example) one finds there is always that pivotal point (and sometimes you have to search for it) which turns the process and makes a piece of writing become a story.

I’ll quote as an example the story of Cinderella, simply because it is one we all know. What is the pivotal point in that story which has ensured it lasts forever? If you think about it, it is the loss of Cinderella’s glass slipper as she runs from the ball as the clock chimes midnight. Think about it. If she hadn’t lost the slipper, she would have gone home, all her finery would have disappeared and it would be an anecdote. (‘I went to the ball after all and had a good night out.’) By losing the slipper, the Prince is given the opportunity to find the wearer, which makes possible the ‘happy ever after’.

Often when writing a story, I have found it didn’t quite work, and almost always it is because I have not found that pivotal point which will make the story move, to bring about the satisfying (or horrifying or whatever) ending. This pivotal point does not have to be in any particular place in the story, and it does not have to be an action or event, it can simply be a change in thought processes, but I do believe it has to be there.

Well I’m sure some people disagree with me, and if you do I’d love to hear why you think I’m wrong. When do you think a piece of writing deserves the title ‘STORY’ ?

Helen Spring

If one studies acknowledged masters of the short story, (I am thinking of Guy de Maupassant or the American writer O. Henry, for example) one finds there is always that pivotal point (and sometimes you have to search for it) which turns the process and makes a piece of writing become a story.

I’ll quote as an example the story of Cinderella, simply because it is one we all know. What is the pivotal point in that story which has ensured it lasts forever? If you think about it, it is the loss of Cinderella’s glass slipper as she runs from the ball as the clock chimes midnight. Think about it. If she hadn’t lost the slipper, she would have gone home, all her finery would have disappeared and it would be an anecdote. (‘I went to the ball after all and had a good night out.’) By losing the slipper, the Prince is given the opportunity to find the wearer, which makes possible the ‘happy ever after’.

Often when writing a story, I have found it didn’t quite work, and almost always it is because I have not found that pivotal point which will make the story move, to bring about the satisfying (or horrifying or whatever) ending. This pivotal point does not have to be in any particular place in the story, and it does not have to be an action or event, it can simply be a change in thought processes, but I do believe it has to be there.

Well I’m sure some people disagree with me, and if you do I’d love to hear why you think I’m wrong. When do you think a piece of writing deserves the title ‘STORY’ ?

Helen Spring

Wednesday 21 January 2015

Year of Anniversaries

This is a year of significant anniversaries in English history. In 1215 King John was presented with Magna Carta, or the Great Charter, by barons who were in rebellion against him. He repudiated it soon enough, claiming that his oaths were sworn under duress and therefore not binding. The barons were interested only in their own grievances, not those of the whole population, and it is debated whether the charter contained anything new, or was just a statement of what the barons believed to be established custom which the king was ignoring.

Nevertheless, Magna Carta has come to be seen as an important step in the evolution of the English, later British, constitution, and of limitation of the power of the monarchy. Its most famous clauses guaranteed free and fair access to justice for all free men:

'No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land. To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice.'

This year is also the 750th anniversary of Simon de Montfort summoning the knights of the shire and the burgesses of the towns to Parliament for the first time - the origin of the House of Commons. Again, de Montfort was a baron in rebellion against the king, then Henry III, and probably more interested in his own grievances than in long term constitutional reform. But like Magna Carta, de Montfort’s action has taken on a much greater significance than was intended at the time.

This year is the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt, in which a small English army led by Henry V defeated a much larger French force. Henry V’s position in France could not be maintained under Henry VI. The greatest long term consequences of the victory at Agincourt were the opportunity it provided for Shakespeare to write some rousing speeches and the marriage of Henry V to the French princess Catherine de Valois. Her second marriage produced the Tudor dynasty, which had such an impact on English history.

It is also the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, which finally broke the power of Napoleon. Although it was not appreciated at the time, the battle ended the long series of wars between Britain and France.

These are the anniversaries surrounding which there are events, books and articles and television programmes. But they are not the only anniversaries this year which are worth noting.

In 1065, Edward the Confessor’s Abbey of St Peter’s at Thorney Island was consecrated - the West Minster.

1315 was the start of the Great Famine which continued into the 1320s. Climate change brought cold, wet summers and bad harvests causing high prices and food shortages.

In 1715 James Edward Stuart, the 'Old Pretender', led a rebellion aimed at deposing the Hanoverian George I and replacing the Stuarts on the throne.

In 1765, HMS Victory was launched at Chatham Dockyard.

Several significant events happened in 1865. Among others, Lord Palmerston, Prime Minister and former Foreign Secretary, died. He had dominated British foreign policy for more than thirty years. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson qualified as Britain’s first woman doctor. And Crossness Pumping Station opened. It was part of Joseph Bazalgette’s sewage system which had a major impact on the health of London.

In 1615 Pleasance Caporne, widow, of Brimpton in Berkshire, died. So did William Keate, a weaver of Newbury in Berkshire and Thomas Segrave, a yeoman of Helpringham in Lincolnshire. They are not famous. We do not know if they were exceptionally good or clever people or if they performed any heroic acts. But they lived and died and possibly have descendants who are alive today.

While it’s right to remember the great achievements, the events that had a national and long lasting impact, we should also remember the millions who have made their own contributions to their communities and to the life of the nation, over millennia.

Thursday 1 January 2015

New year, new writing

A time for a writer to take stock of achievements to date and plan the next stage of his or her writing career. For me, as well as being a new year, in a few days it will also be the anniversary of publication of my first Kindle novel. I now have three published. It's so far been a very positive, even (in a modest way) profitable, experience.

Independent e-publishing is a great time saver for an author. No need to research potential agents and publishers, put together submissions, wait for them to come back, then start the whole process again. Then, even if a deal is forthcoming, wait again for the book to be published.

For e-publishers, the big unknown going into the New Year is how sales will be affected by the new EU VAT regulations. The VATman will be taking a bigger share of the retail prices of e-books. (Print books are exempt from VAT.) Independent authors, who set their own prices, have the choice of leaving them the same, and making less money per book sold, or increasing them, and possibly losing sales.

I didn't make as much progress with my next novel during the autumn as I'd hoped. I had a muscle injury which took a long time to clear up which prevented me from sitting comfortably at the computer for any length of time. It made me appreciate how incapacitating quite minor injuries could have been in the past, when so many people did manual work and small every day tasks required much more physical effort than they do to today. Making a hot drink could require pumping water and carrying coals, instead of turning on a tap and flicking the switch on the electric kettle.

The next novel I plan to publish is a crime story set in Victorian London. After that I hope there will be another story featuring the main characters from The Plantagenet Mystery.

At the back of my mind I have an idea for a historical mystery with a different setting and central character. I'm a long way from being ready to write it, but from time to time I think about it and make a few notes. The character is in his thirties and happily married. In a historical setting, this would mean there would be children. I don't want the parents to ignore their children (and they are not of high enough status for the children to be spending all their time with nursemaids, governesses and tutors). But neither do I want the children to take over the story!

On an entirely unrelated subject, in the last couple of days I've tried to explore two different online archive catalogues. Neither has a browse function, only a search. I don't want to search for a specific item, I want to browse to look for anything that might be useful or interesting to me. One of these catalogues doesn't even have a brief outline of the structure and content of the archive. How is one supposed to search if one doesn't know what there is to search for?

Independent e-publishing is a great time saver for an author. No need to research potential agents and publishers, put together submissions, wait for them to come back, then start the whole process again. Then, even if a deal is forthcoming, wait again for the book to be published.

For e-publishers, the big unknown going into the New Year is how sales will be affected by the new EU VAT regulations. The VATman will be taking a bigger share of the retail prices of e-books. (Print books are exempt from VAT.) Independent authors, who set their own prices, have the choice of leaving them the same, and making less money per book sold, or increasing them, and possibly losing sales.

I didn't make as much progress with my next novel during the autumn as I'd hoped. I had a muscle injury which took a long time to clear up which prevented me from sitting comfortably at the computer for any length of time. It made me appreciate how incapacitating quite minor injuries could have been in the past, when so many people did manual work and small every day tasks required much more physical effort than they do to today. Making a hot drink could require pumping water and carrying coals, instead of turning on a tap and flicking the switch on the electric kettle.

The next novel I plan to publish is a crime story set in Victorian London. After that I hope there will be another story featuring the main characters from The Plantagenet Mystery.

At the back of my mind I have an idea for a historical mystery with a different setting and central character. I'm a long way from being ready to write it, but from time to time I think about it and make a few notes. The character is in his thirties and happily married. In a historical setting, this would mean there would be children. I don't want the parents to ignore their children (and they are not of high enough status for the children to be spending all their time with nursemaids, governesses and tutors). But neither do I want the children to take over the story!

On an entirely unrelated subject, in the last couple of days I've tried to explore two different online archive catalogues. Neither has a browse function, only a search. I don't want to search for a specific item, I want to browse to look for anything that might be useful or interesting to me. One of these catalogues doesn't even have a brief outline of the structure and content of the archive. How is one supposed to search if one doesn't know what there is to search for?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)